From Zero to Hero: Denim’s Long Journey from the World of Workwear to the Centre of Fashion

Part THREE of a Three-Part Series on Denim History

By Bryan Szabo

We’ve come at last to the final chapter in our story. In the first part of this three-part series on the history of denim, we looked at denim’s roots, first as a European workwear fabric, and then as an American one that was all but perfected by Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis in 1873. In the second part, we looked at denim’s movement into the modern age, ending with the dude ranchers of the ‘30s, who were the first to wear denim as a lifestyle product. We’ll close the story with a look at denim’s entry into the mainstream of fashion, beginning with a handful of radicals and artists in the 1930s.

Gathering Steam

Between the first and second world wars, denim began to wiggle free of its workwear roots. Dude ranchers had adopted denim cowboy duds, which led to denim’s first appearance in Vogue, but this was a playful form of dress-up mostly practiced by the wealthy leisure class.

For some, though, denim was worn earnestly and even passionately—often as a display of solidarity with the working class. Mexican muralist Diego Rivera (best remembered today as the husband of Frida Kahlo) was frequently photographed wearing denim in the 1930s, blurring the line between himself and his working-class subjects. Many of these photographs were taken while the artist was at work, with his denim splattered with paint. In other photos, though Diego seems to be taking his leisure in chore coats and overalls that look more pristine. He had clearly incorporated denim into his personal style.

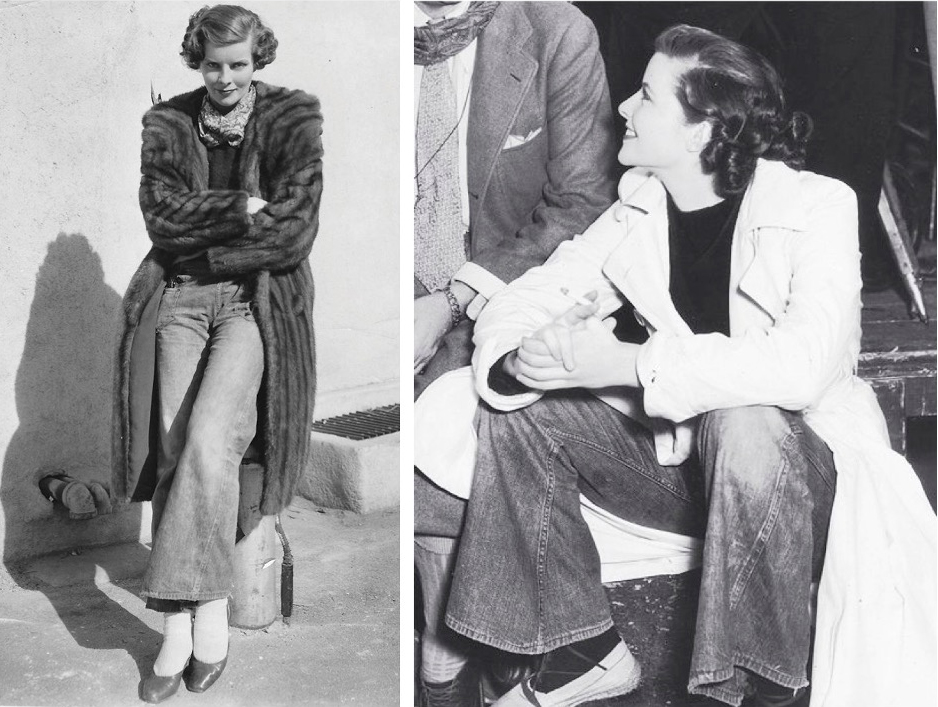

Left-leaning artists like Rivera weren’t the only ones to experiment with denim in the ‘30s. Feminist icon Katherine Hepburn, the first woman to wear trousers on the big screen, frequently arrived on set wearing a beautifully faded pair of bell-bottom dungarees. Studio bosses were so incensed with her attire (for women to wear trousers at all was a radical gesture) that they stole the pants from her dressing room. She returned to set in her underwear and refused to cover up until her jeans were returned to her (they quickly reappeared in her dressing room).

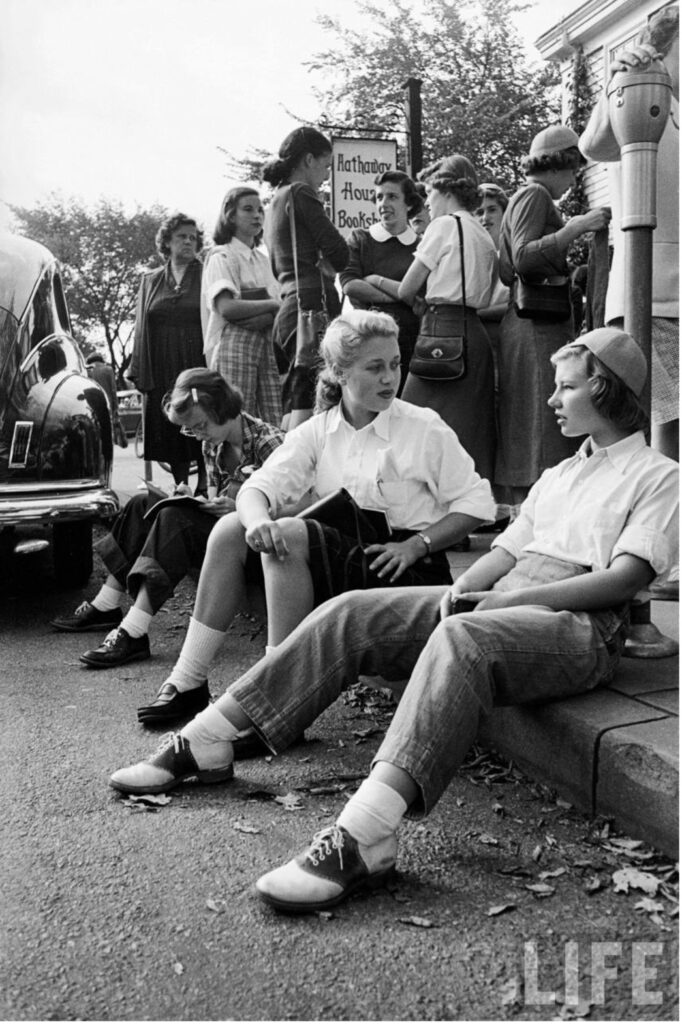

Thanks to a handful of fashion-forward trailblazers who pioneered stylish denim looks in the ‘30s, denim began to gather steam. At the beginning of the ‘40s, starting on west-coast college campuses and quickly spreading eastward, young women started combining loose-fitting denim trousers cuffed above the ankle with bobby sox and either loafers or scuffed up saddle shoes. Students of Wellesley College showed off the style, dubbed the “sloppy look” by its critics, in a 1944 issue of Life magazine, leading to much hand-wringing and pearl-clutching from America’s status quo defenders.

The outrage added fuel to the fire. Denim was not just stylish, it was also rebellious—and, as the new decade dawned, rebellion was coming into fashion.

Denim’s Defining Age

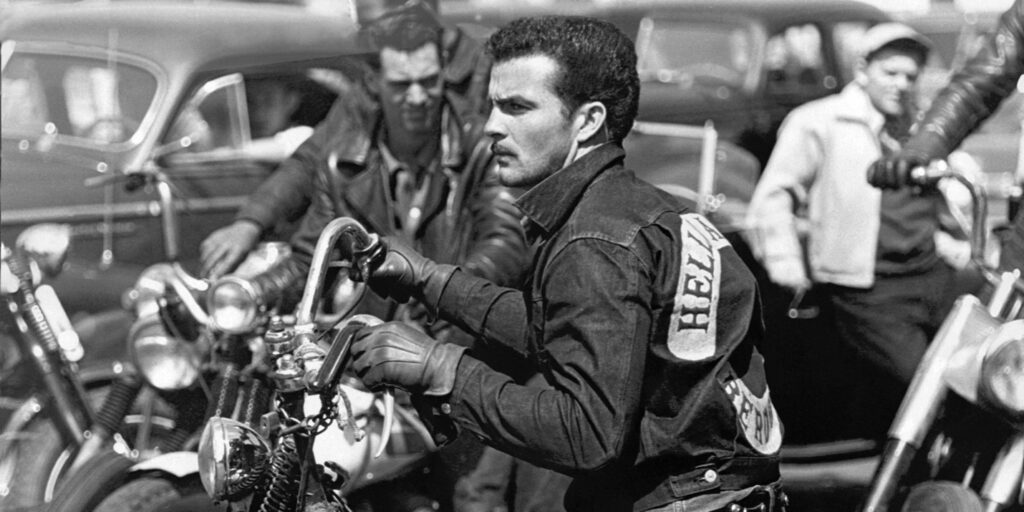

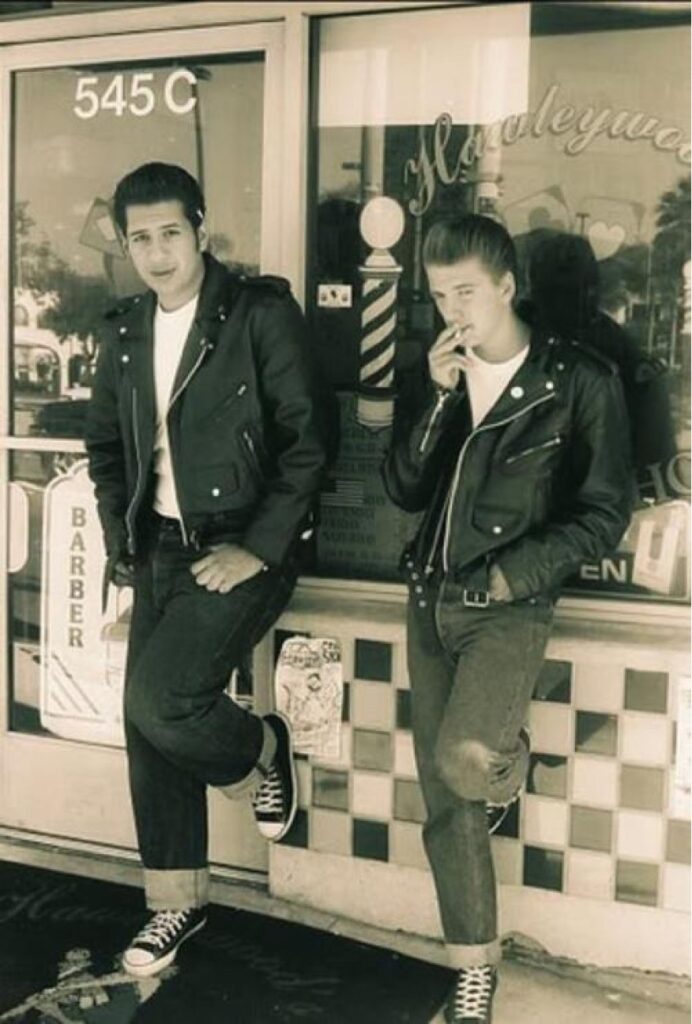

In the years following the war, many returning servicemen struggled to find their place in America. Conventional wisdom said that, upon their return to America, they should seek contentment in the nuclear family, the nine-to-five job, and the suburban home. Some couldn’t see the appeal. With their brothers in arms, they had stormed beaches, piloted high-octane war machines, and liberated Europe. The American Dream couldn’t raise their pulses. They didn’t want the white picked fence. They wanted thrills and camaraderie, and they found it in outlaw motorcycle clubs. They let their hair grow, exchanged their wool uniforms for denim and leather ones, and became a fixture on America’s highways.

The outlaw bikers, with their bravado and flippant contempt for authority, modelled a kind of absolute freedom that made them uniquely fascinating. Their look was imitable and inexpensive, which helped it spread quickly. The foundational pieces that made up the biker’s look—slim-fitting jeans, a tee (usually white), and either a leather or a denim jacket—became the bedrock of a distinctly American style that has remained, in some form or another, in vogue for the better part of a century. The motorcycle may have been optional, but the denim was essential.

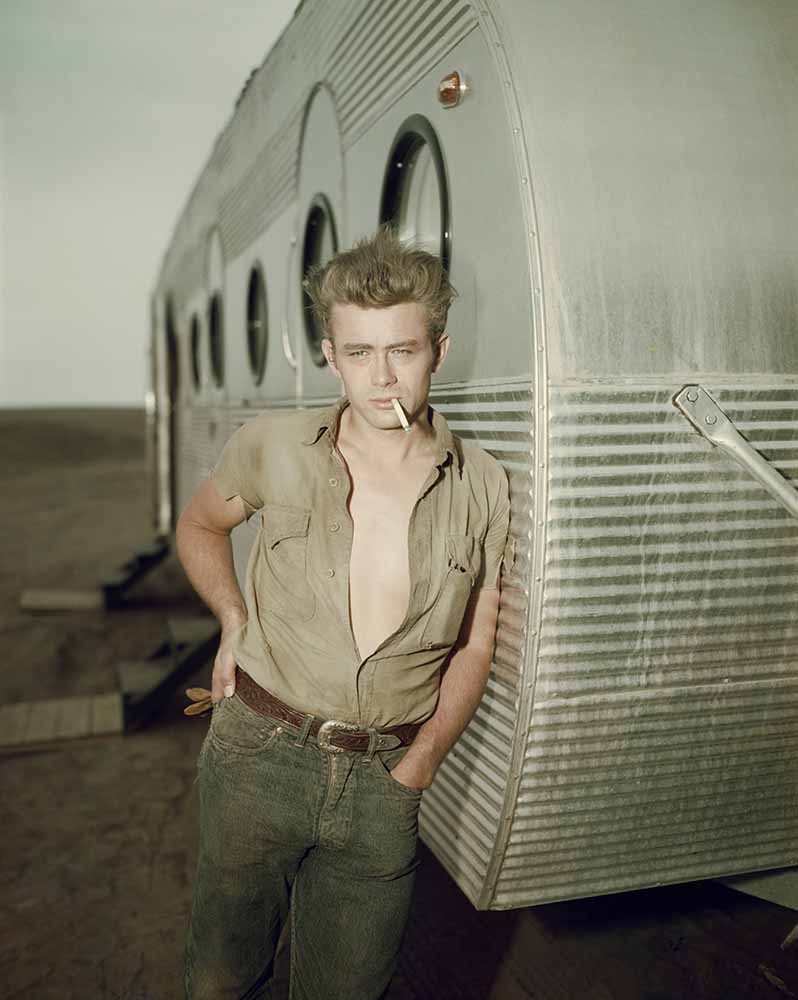

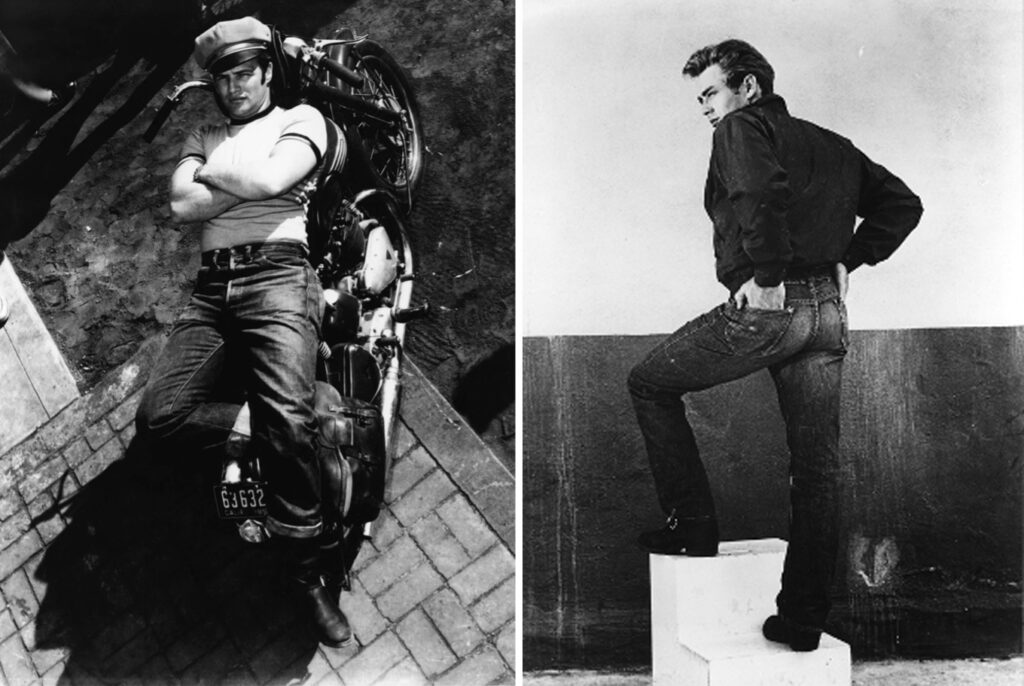

Denim saturated nearly every form of popular entertainment in the ‘50s. On the big screen, it had long had a secure foothold in the western genre, but in the 1950s, it began appearing in films set in the present. In 1953, Marlon Brando played Johnny Strabler in The Wild One. Though the film itself was mediocre, it set a precedent for rebellious leads. James Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause would follow just a few years later, further cementing denim’s starring role in American culture.

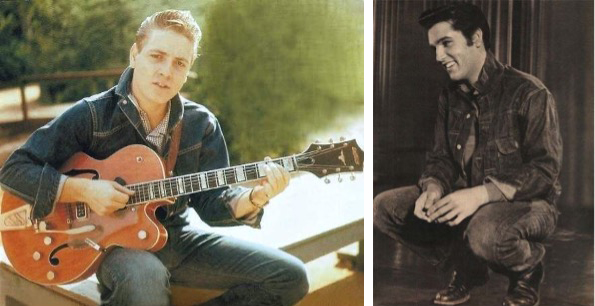

The new rock and roll sound of the ‘50s arrived draped in denim. Elvis Presley may have preferred tailored suits to workwear (blue jeans apparently reminded him of the poverty of his youth), but he understood denim’s undeniable sex appeal. When the cameras were rolling, he donned double denim, wearing it with as much aplomb as anybody ever has. Some of his contemporaries (most notably, crooner Bing Crosby and rocker Eddie Cochran) made double denim the cornerstone of their looks, both on screen and off.

In the closing years of the ‘50s, many of the young rebels who helped make denim the most quintessentially American fabric traded in their jeans for grey, wool suits, but the generation that followed them would once again place denim at the centre of a countercultural revolution. The hippies picked up where the greasers and rockers left off, digging their parents’ well-worn jeans out of the closet and turning them into personalized works of art. Distressed, patched, and embroidered denim became the uniform of an optimistic youth culture that, in 1969, reached its zenith in a muddy farmer’s field outside Woodstock, New York.

Levi’s marketers capitalized on the moment with a now-iconic advertisement that seemed to capture the denim-loving Woodstock crowd. In fact, the picture was taken at a 1970 music festival in The Netherlands, but this only makes the advertisement’s underlying message more powerful. With the aid of popular musicians and other powerful cultural figures, denim had taken over the world.

Here, There, and Everywhere

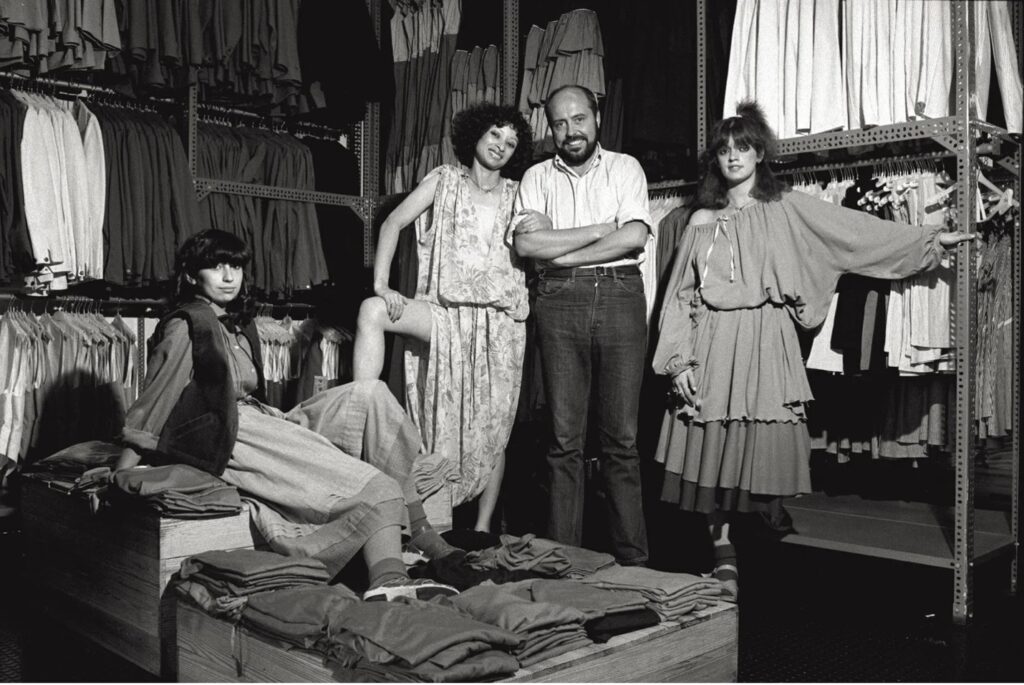

The end of the ‘60s also marked denim’s debut into the world of couture fashion. Vogue featured a 14-page feature on denim skirts in 1968, and Yves Saint Laurent used the fabric in a 1969 collection, becoming the first designer to use denim on the catwalk. Other designers were soon following suit, triggering a goldrush of upscale designer denim that began in France with MacKeen and in Italy with designer Elio Fiorucci. The designer denim duds sold for three times what imported Levi’s were selling for, and there was no shortage of customers willing to pay a premium for the pairs. American designers saw the opportunity and leapt into the luxury denim space with both feet. Gloria Vanderbilt and Calvin Klein are often credited with inventing designer denim, but the Europeans were the true pioneers.

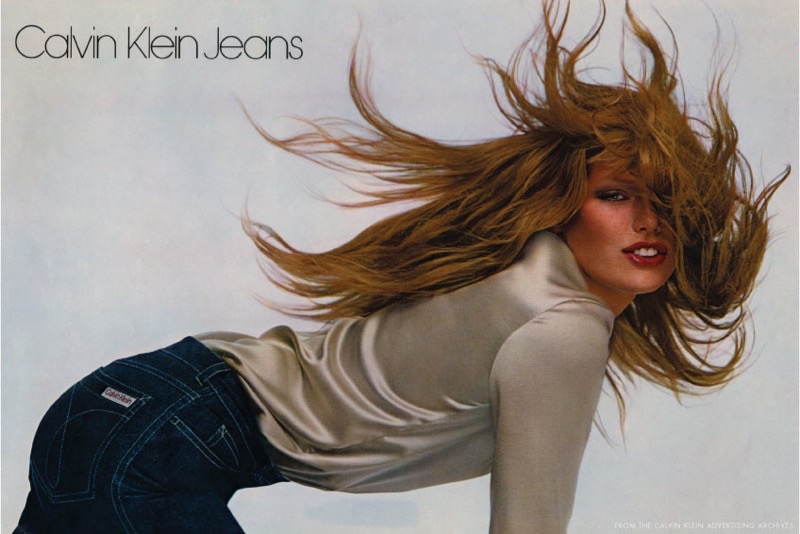

What separated the Americans from their overseas competitors was the former’s ability to advertise denim provocatively. In 1978, Klein unveiled a Times Square billboard featuring model Patti Hansen on all fours tossing her hair back as she looked towards the camera. The billboard, which remained in Times Square for four years, was a watershed moment for both the denim and the advertising industries. The product itself faded into the background, with sex taking its place in the foreground. Klein would repeat the trick in 1980 with a made-for-TV spot featuring fifteen-year-old Brooke Shields. The controversial ads ginned up outrage aplenty, but the adage proved true: there’s no such thing as bad publicity. The moral panic only helped Klein sell more pairs.

It’s at this point that the story will start to become a familiar one for most of us. The rise of designer denim signalled denim’s emergence as a truly global commodity with a rotating carousel of popular brands fighting for their share of a global denim market worth an estimated $75 billion annually. Jeans have formed an only superficially changing bedrock of casual style for generation after generation of men, women, and children of all ages.

This is not to say that denim designers have run out of ideas or that manufacturers can no longer innovate. Visit a trade show like Munich’s Bluezone, which is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, and it becomes immediately apparent that the denim industry is trying to see around the corner to the next big sea change in the fashion industry. They’re seeking sustainable solutions, trying to produce one of the world’s most popular products in responsible and ethical ways. Together, they’re ensuring that denim’s story has no end.