From Zero to Hero: Denim’s Long Journey from the World of Workwear to the Centre of Fashion

Part One of a Three-Part Series on Denim History

By Bryan Szabo

Denim has planted its feet so firmly in our notions of casual style that it might feel as though it’s always been with us. Few are old enough to hold in their living memory the moment when the intertwined worlds of fashion and style began their long love affair with denim; fewer still can remember the time before this, when denim was purely a rugged working man’s fabric.

To refresh our memories, let’s take a stroll down the long and winding road of denim history. In this article, the first of a three-part series, we’ll look at the foundational history of denim—from the European roots of the fabric up to Strauss and Davis’s patented riveted waist overalls.

An American Classic with European Roots

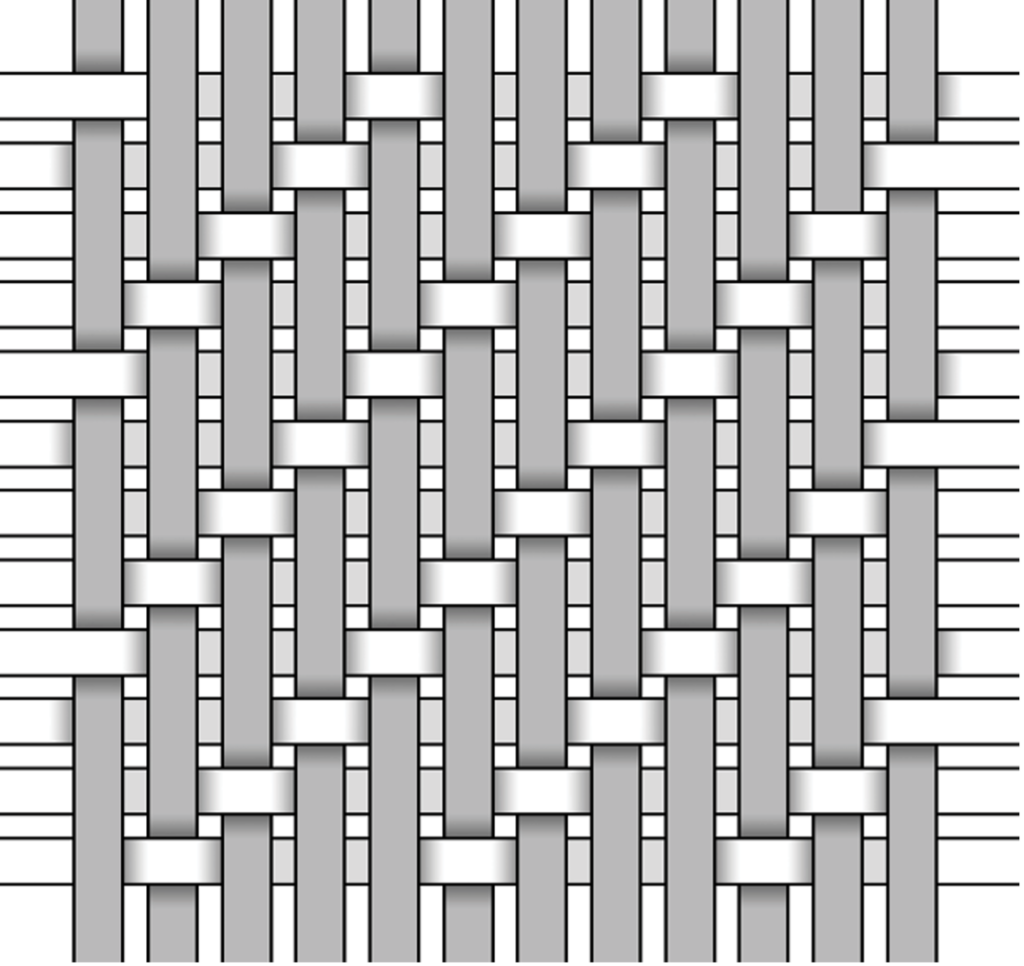

Denim’s history doesn’t have a distinct starting point. The fabric that, today, we call denim is a robust warp-faced twill that shares features with textiles that have been popular since at least the sixteenth century. Usually made entirely from cotton, today’s denim combines indigo-dyed warp yarns and undyed weft yarns. There have been countless variations and innovations through the years that have stretched (literally and figuratively) our understanding of what denim is, but the classic twill with one side dark and the other side light remains the most popular and recognizable version of the fabric.

Denim takes its name from a blend of cotton and wool called Serge de Nîmes that supposedly first appeared in the Southeast of France in the sixteenth century. Its origins aren’t cut and dry, though. It’s unclear whether the fabric actually debuted in France, or if it was an English invention with a French-sounding name. English weavers produced large quantities of Serge de Nîmes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and its French name may have been a marketing ploy—an attempt on the part of English manufacturers to give their domestic product an exotic and luxurious cachet.

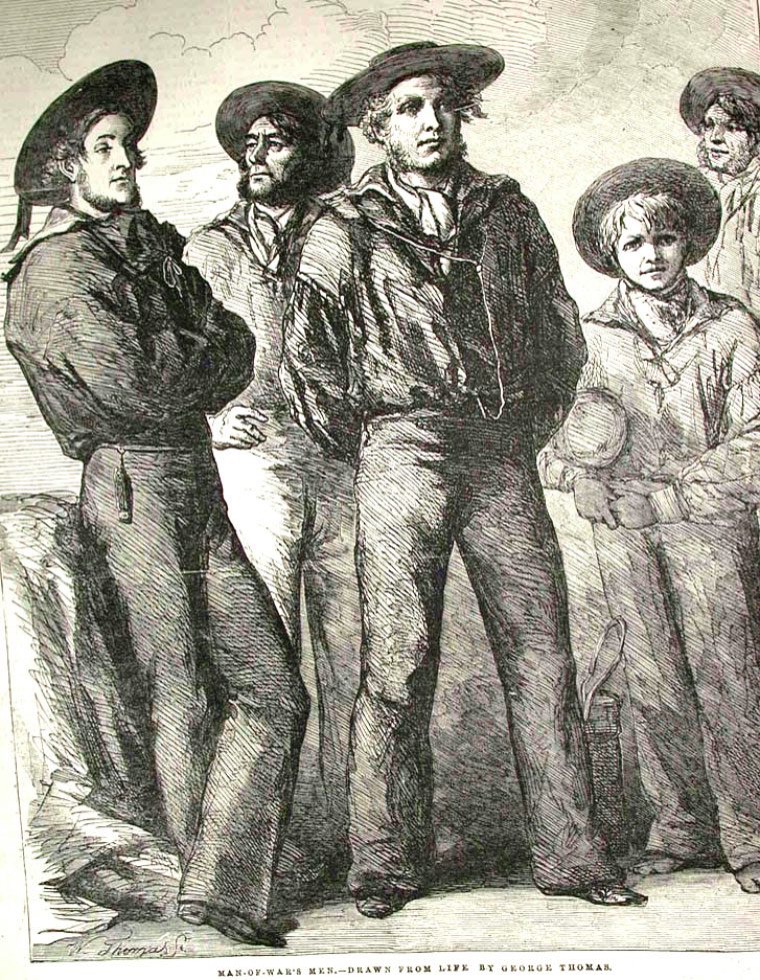

On the other side of Europe, another woven textile—this one a lighter blend of cotton, wool, and occasionally silk—was gaining traction in the popular seaport of Genoa. Like denim, its English name reflected its port of origin. Jean (the word has been in the English language since at least 1567) was probably first woven in Italy, and it became the fabric of choice for Genoese seaman’s trousers. The inexpensive workwear fabric didn’t stay in Italy for long, though. It was being imported into England in large quantities by the end of the sixteenth century.

Denim and Jean in the New World

As Europeans crossed the Atlantic to the new world, jean and denim came with them. America was forging an identity distinct from Europe, and, just as denim would become a defining feature of the American West, denim and jean played a role as the nation put down manufacturing roots in the Northeast. Jean was so popular in the new world that America’s first industrial textile mill, The United Company of Philadelphia for Promoting American Manufactures (founded in 1775), listed jean as their primary output. In the years after the American Revolution, the company’s factory, which included 26 power looms, was producing thousands of yards of cloth each month, much of it jean.

While most historians look further north to the New England states to locate ground zero in America’s Industrial Revolution, some historians suggest that it was this jean-producing United Company factory in Philadelphia where the wheels of American industry first began to turn. Wherever that revolution started, jean and denim were important fabrics for the young nation’s thriving textile industry, which was soon gathering steam in New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

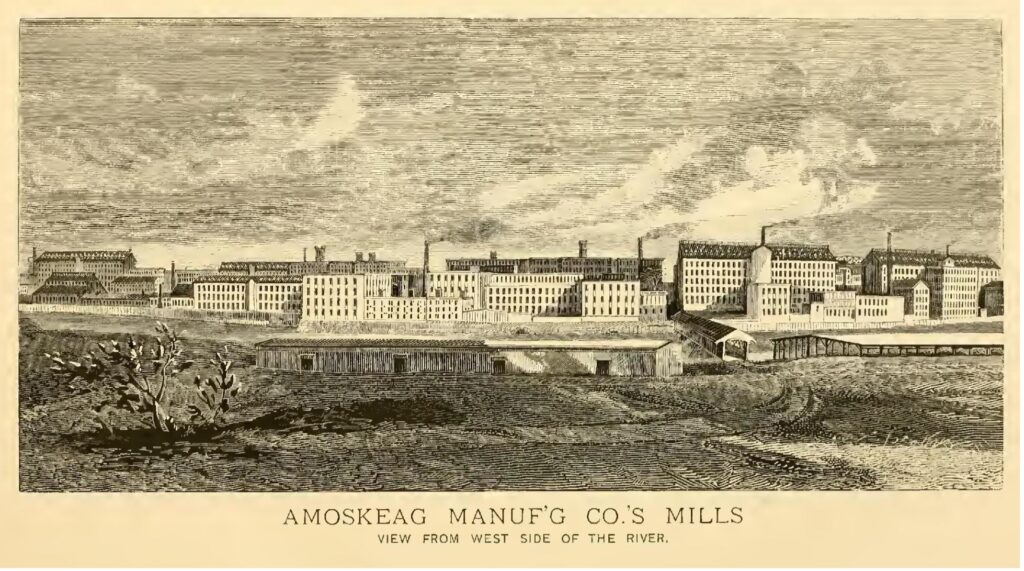

One New England mill stood head and shoulders above the rest. Amoskeag Manufacturing Company of Manchester, New Hampshire was, by the middle of the nineteenth century, producing what was arguably the world’s best denim. Founded in 1831, the mill sat at the centre of a massive complex, including homes, parks, churches, and schools. Swelling the local population from a mere 877 souls in 1830 to 70,000 by 1910, it was essentially a city unto itself with chattering looms at its heart.

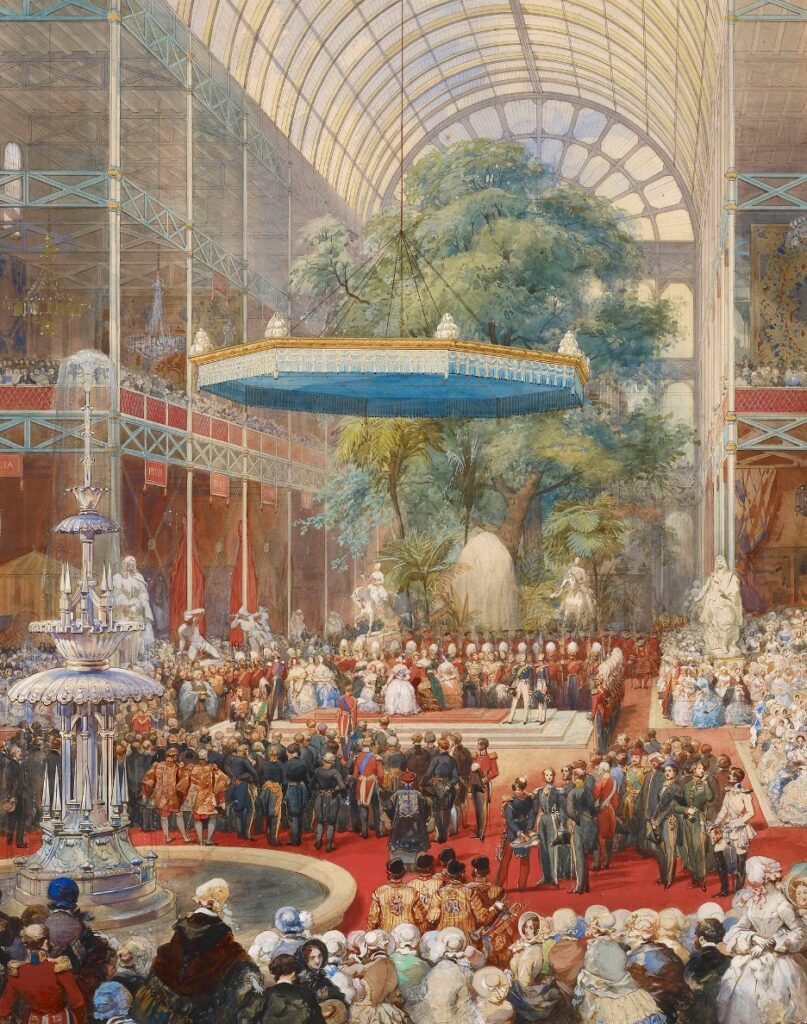

In 1851, Amoskeag exhibited some of their finest textiles, including denims, ginghams, and flannels, at the Great Exhibition in London. Held in the Crystal Palace and inaugurated by Queen Victoria, the Great Exhibition was the first in a series of World’s Fairs that brought together the nations of the world to exhibit their technological or cultural achievements. Judges at the fair singled out Amoskeag’s denim for special recognition, giving the mill not just the first prize, but the only prize for textiles awarded at the fair.

With the blue ribbon to back up their claims of quality, Amoskeag became the mill of choice for a growing number of manufacturers and wholesalers who were looking for the strongest cloth that could be used to manufacture clothing for working men. One dry goods wholesaler, a newly arrived Bavarian immigrant who had set up shop in San Francisco, would use Amoskeag’s denim to make one of history’s most iconic products. His name: Levi Strauss.

Workwear Perfected

Levi Strauss did not invent blue jeans. He merely perfected them. In the early 1850s, when Strauss arrived in San Francisco, the Californian Gold Rush was in full swing. It became clearer by the day to merchants in the Northeast that the Gold Rush was not some flash in the pan. Lucrative opportunities were there for those with the means and the hutzpah to seize them.

Strauss was just one of these. He came to San Francisco in 1853 as an unmarried twenty-four-year-old man, an emissary for his brothers’ successful New York-based dry goods business, with letters of introduction in his pockets. Other dry goods wholesalers had already set up shop along the San Francisco waterfront, but there was, according to Levi’s historian Lynn Downey, “plenty of business to go around.” Strauss received his first shipment of dry goods from New York only weeks after he landed, and he quickly found customers for his goods. Just two years after his arrival, he was sending more than $80,000 worth of gold per annum to his brothers in New York (more than $2 million in today’s currency).

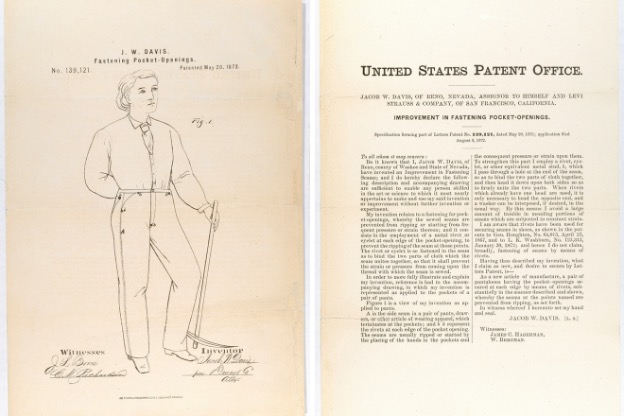

Depending on how you look at it, Strauss was either the shrewdest or the luckiest dry goods wholesaler in San Francisco. In the summer of 1872, he received a letter from a tailor and tinkerer in Nevada named Jacob Davis. Davis, who had earlier ordered bolts of duck canvas from Strauss, said he had found a way to improve the integrity of denim and duck waist overalls. With the aid of a handful of humble rivets, pockets (then prone to ripping at the corners) and the major seam at the crotch could be strengthened considerably. The tailor was already flooded with orders for the pairs he was making in his small shop, and he wanted Strauss’s help to secure the costly patent.

Strauss saw the opportunity and seized it, partnering with the tailor to produce riveted waist overalls in San Francisco, with Davis overseeing production. The reinforced working pants debuted in the summer of 1873 and quickly gobbled up a lion’s share of the market. Thanks to the patented rivets—far stronger than anything else that competitors could produce—rival manufacturers could only watch in dismay as their customers flocked to Levi Strauss.

In the years before the patent expired, Strauss added his iconic two-horse branding and his signature gull-shaped arcuates to his pairs, making them easy for would-be customers to recognize. Further improvements and branding (the fifth pocket on the left side of the seat and the iconic red tab) would appear later in the twentieth century, but the design would remain essentially unchanged. Together, Strauss and Davis had given the world one of its longest-lasting rugged style icons. Perfected at their birth, jeans as we know and love them today had arrived.

We’ll continue the story in the next article, looking at the appearance of the other legacy brands and the movement of denim from the world of workwear to the silver screen and, finally, to the catwalk.