From Zero to Hero: Denim’s Long Journey from the World of Workwear to the Centre of Fashion

Part Two of a Three-Part Series on Denim History

By Bryan Szabo

In the first article in this series, we looked at denim’s history as a sturdy workwear fabric, first in Europe and then in America. The first chapter opened in the sixteenth century and closed with the introduction of Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis’s patented riveted overalls in 1873. We’re continuing the story in part two of our three-part series with a look at the birth of legacy denim brands Lee and Wrangler and the emergence, in the 1930s, of denim as a distinctly western lifestyle product.

The New West and Legacy Denim Brands

When Levi Strauss arrived in San Francisco in 1853, he found a California that still existed on the edge of a ragged frontier. Cities like San Francisco and Sacramento were just beginning to take shape. Gold was drawing hard-scrabble men by the tens of thousands, most of them hoping to strike it rich. According to the 1850 Census, of the 77,631 males then living in California, 57,797 made their living as miners.

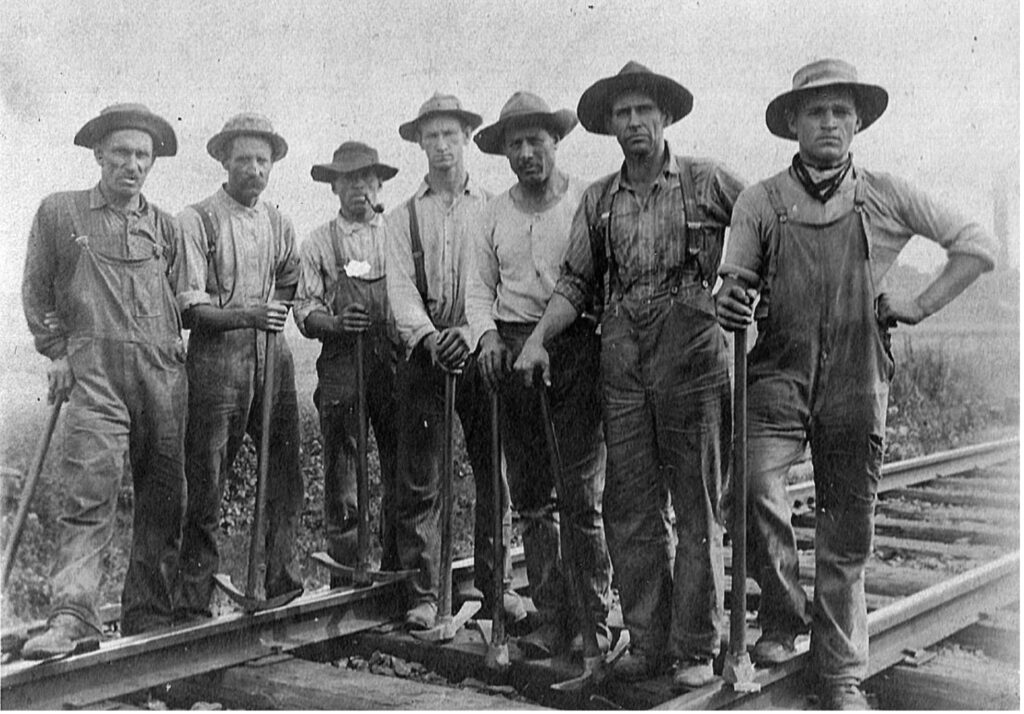

As mined gold became minted gold, California’s cities were transformed into clattering and crowded metropolises. Railroads soon connected East to West, and denim found itself in the middle of the rapid modernization of the American West. Put to work in the mines, on the railroads, and in the factories, the rugged twill became one of the defining features of American industry, which was fast turning the Old West into the New.

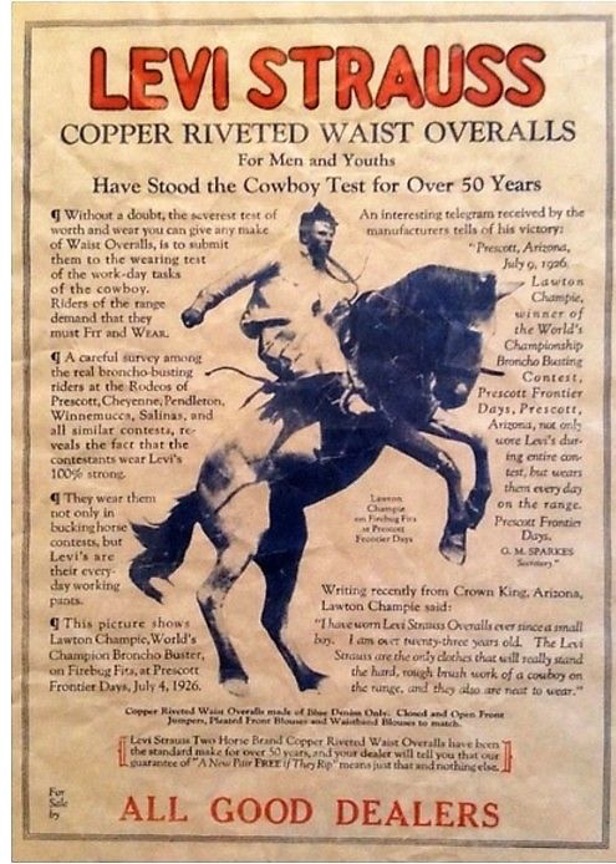

In the process, denim helped make fortunes for Western merchants like Strauss. His San Francisco-based competitors tried to replicate Strauss’s success, but the patented rivets combined with premium Amoskeag denim put Levi’s overalls in their own category. When Strauss and Davis’s patent finally expired in 1892, this set off a late-century riveted workwear goldrush, with brands like Los Angeles’s Stronghold and San Francisco’s Can’t Bust ‘Em and Non-Pareil giving Strauss a run for his money with their versions of rivet-reinforced waist overalls.

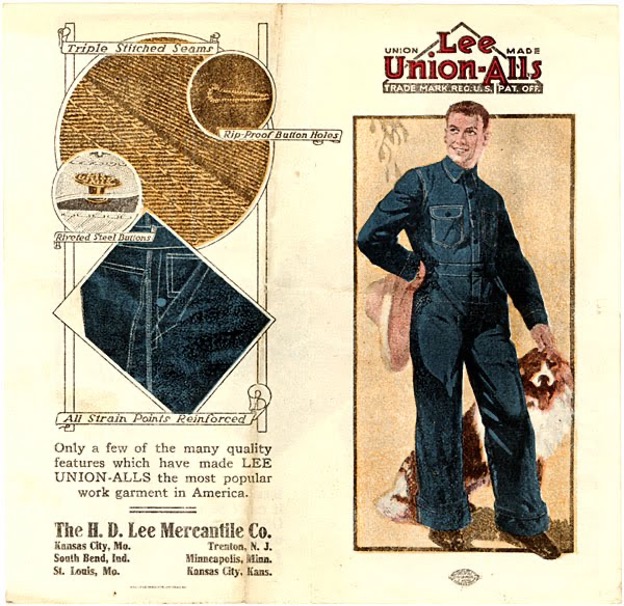

As a new century dawned, a pair of workwear upstarts were kicking up clouds of dust to the east. Henry David Lee founded the H.D. Lee Mercantile Company in 1889 in Salina, Kansas. Beginning as food distributors, the company quickly branched out into supplying other goods, including workwear. Unsatisfied with the quality of denim garments he could procure from other suppliers, Lee started manufacturing his own line of sturdy overalls, jackets, and dungarees in 1912.

The next year, he debuted the Lee Union-All, a denim cover-all marketed to car-owning Americans who needed something they could store under the seat. Whenever the finicky and oil-spitting machines needed roadside repairs, Lee’s Union-All could ensure they arrived at their destination with clean clothes. The spectacular success of the Union-All, propelled by the rapid spread of the automobile, endorsements from the likes of Babe Ruth, and the expanding manufacturing sector, turned Lee into a household name.

In 1926, when the brand debuted their 101Z Rider jeans, specifically designed for life in the saddle, they planted their feet in the rodeo circuit and the emerging western wear market. With their success on both the factory floor and the rodeo ring, Lee climbed to the top of the ladder, becoming America’s largest workwear manufacturer by 1939.

They would soon have formidable competition in the rodeo ring. Founded by brothers C.C. and Homer Hudson in 1904, the Hudson Overall Company had found pools of enthusiastic customers among extremely hard-wearing railroad workers. Legend has it that one railroad company was so impressed with Hudson Overalls that they sent a large railroad bell to the company’s headquarters as a thank you. After years in the factory, the bell was covered in indigo-tinged cotton dust, giving the company the name that it adopted in 1919: Blue Bell.

In 1943, Blue Bell acquired the Casey Jones Company and their portfolio of brand names. Included among them was Wrangler, and, in 1947, Blue Bell used this brand name when they introduced their 13MWZ, a pair of jeans cut and trimmed for cowboys with the help of legendary western tailor Rodeo Ben. Endorsed by world champion cowboy Jim Shoulders and later by the Pro Rodeo Cowboy Association, Wrangler would grab the brass ring, becoming the quintessential cowboy jean.

Wrangler’s victory in the rodeo ring came at tail end of a period of fierce competition between Levi’s, Lee, and Blue Bell. Cowboys had discovered the virtues of denim around the turn of the century, and the three brands locked horns in a long-lasting battle for the western workwear market. They spent lavishly on hospitality tents, hosting the rodeo stars and plying them with free drinks and clothes in hopes of securing their endorsements, and denim brands began to advertise using familiar western motifs.

The target of these advertisements was largely the working men who, like the factory workers, railway employees, and farmers, exploited the full range of denim’s durability. In the 1930s, though, Levi’s saw and pounced on a new kind of opportunity in the West. For the first time, denim would be marketed, not just as a working man’s commodity, but also as a lifestyle product.

Denim and the Dudes

America’s long love affair with denim shares a genealogical root with its much older love affair with the West. It was love at first sight. Hunters, pathfinders, and adventurers sent back accounts from the frontier, and these captivated readers in the East. In the nineteenth century, first on the stage and then in outdoor arenas, audiences flocked to wild west shows, making household names of sharpshooters and frontier toughs like Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickok, Annie Oakley, and Calamity Jane.

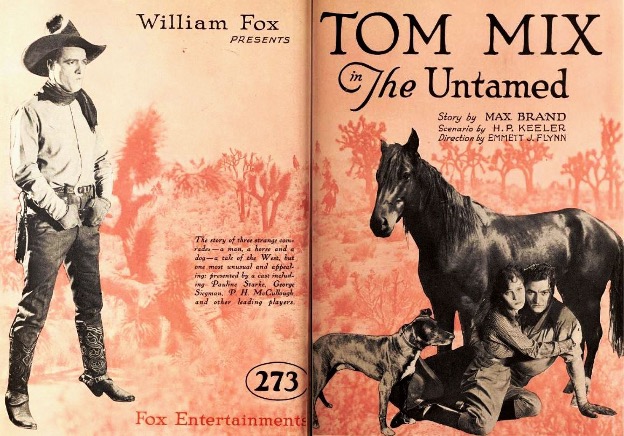

At the turn of the century, these shows gave way to silent films, with the era’s brightest stars carrying six shooters and wearing ten-gallon hats. The extras and bit-players were often working cowboys, and they would arrive on set wearing their well-worn jeans. They were the first men to wear denim on the big screen, and, in the 1920s, the stars would follow suit. Early western icons like Tom Mix and Harry Carey delighted audiences with their gritty, denim-clad men of action. Denim took centre stage; like the heroes who wore it, it kept cool under pressure and had strength to spare.

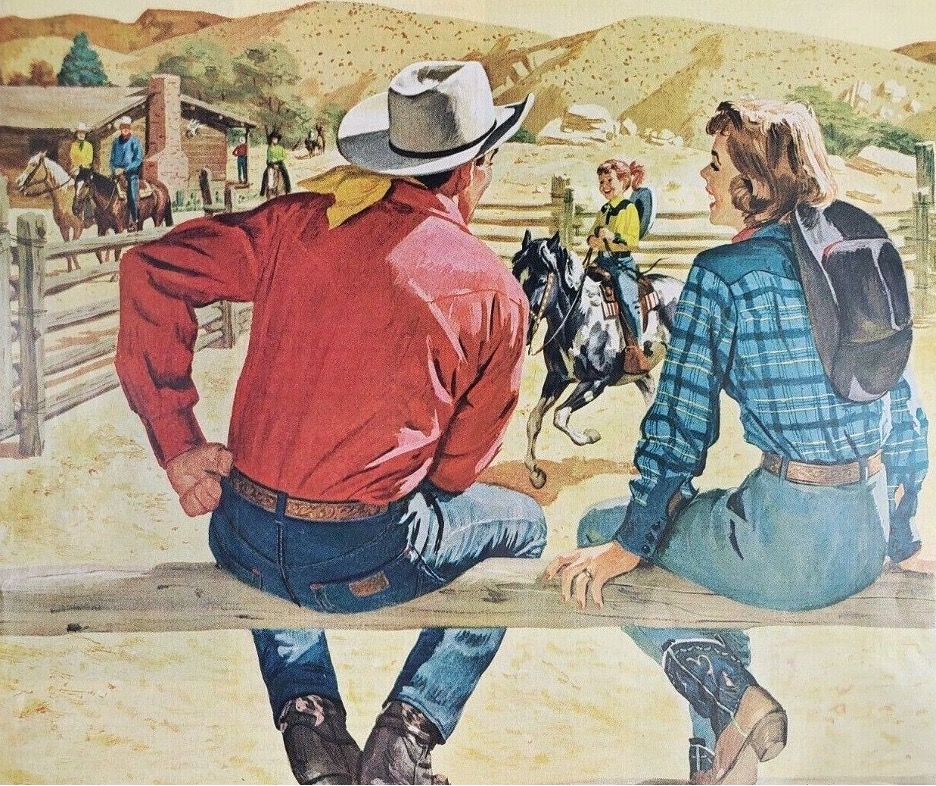

It still wasn’t enough, though. A growing number of Americans wanted a more authentic experience of the West than the movie theatre or the rodeo ring could offer. They wanted something more immersive—an unmediated experience of the cowboy life. They found it on the dude ranches. Rancher Howard Eaton had opened the first dude ranch in Wyoming in 1904, and he quickly found that paying tourists were more lucrative than cattle. Other ranchers were quick to follow Eaton’s lead, and by the 1930s, would-be dude ranchers were spoiled for choice.

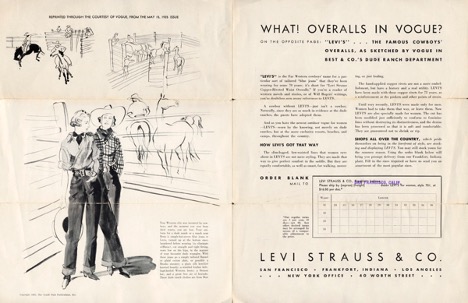

Visitors to these ranches wanted to look the part, and jeans become de rigeur for those who wanted to blend in with the cowboys. Levi’s were not yet available east of the Mississippi, so Abercrombie and Fitch, then New York’s premier outdoor outfitters, began placing mail orders for Levi’s on behalf of their customers. Levi’s was quick to notice this new market, and they responded by revolutionizing the way that jeans were marketed (and to whom).

A significant percentage of the dude ranchers were women. Some came with their husbands, but the ranches were also a destination for women seeking independence. Nevada, a dude ranching hotbed, had the most relaxed divorce laws in the nation, so socialites from Manhattan or Philadelphia would take up residence on a Nevada dude ranch for a couple of weeks and leave with divorce papers in hand. Women found empowerment and freedom on the dude ranches, and Levi’s saw the potential in this.

Levi’s introduced Lady Levi’s in 1934—the first jeans designed specifically for women. Profiled in a 1935 Vogue article about what to wear on the dude ranch, the softer and suppler version of Levi’s moved denim into an entirely new category. Jeans were suddenly fashionable. Connected to a feeling, a look, and a lifestyle, denim’s primary selling feature up to that point (it’s durability) was an afterthought. Jeans now provided a sense of belonging and a feeling of comfort. They were, said the editors at Vogue, “worn by the knowing”. For the first time, jeans were hip.

Denim was turning the corner, transforming from something working men needed into something the leisure class wanted. Yes, it was a form of dress-up that would have been as out of place on Main Street as a ten-gallon hat, but the dude ranchers didn’t abandon their dusty duds when they left the ranches. They brought their jeans home with them, which meant denim was starting to trickle into urban spaces and the suburbs. Its next stop would be on university campuses. This is where we’ll pick up the story in the final article in this series.